Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

It was not a rare thing for young men to walk the entire distance from Massachusetts to Ohio, carrying a few indispensable articles upon their backs, in a white canvas knapsack. One or more of these knapsacks might be found in almost every neighborhood during the early years, cherished as mementos of such pedestrian feats. One young man brought in his ‘pack,’ from Massachusetts to this county, a pair of iron wedges, implements more valuable to him than a wedge of gold.

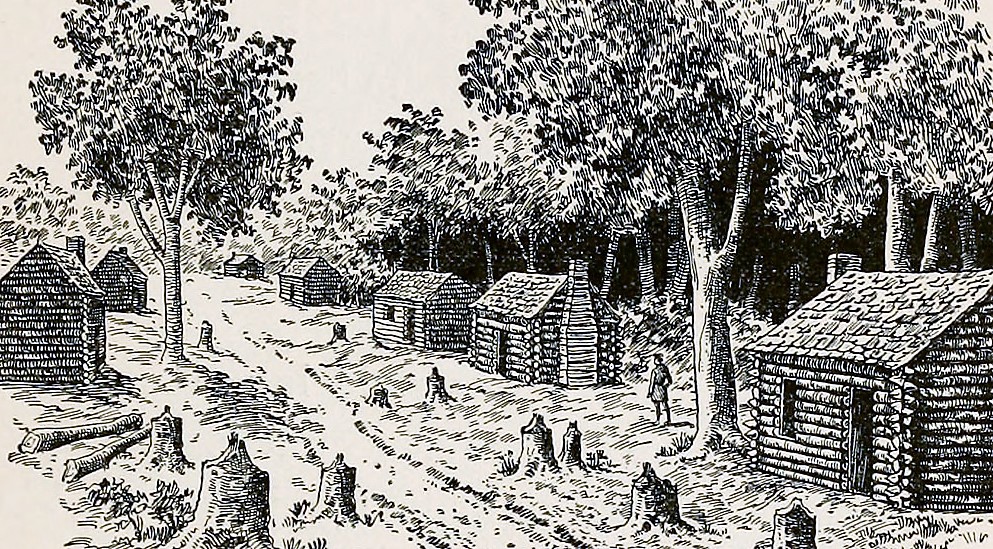

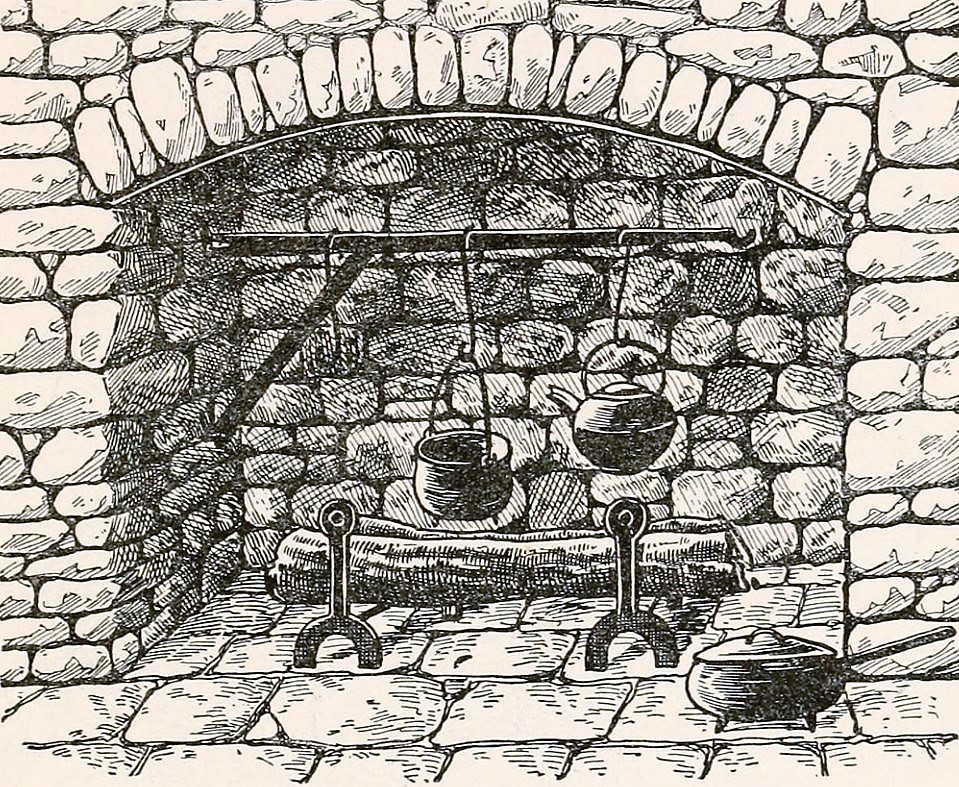

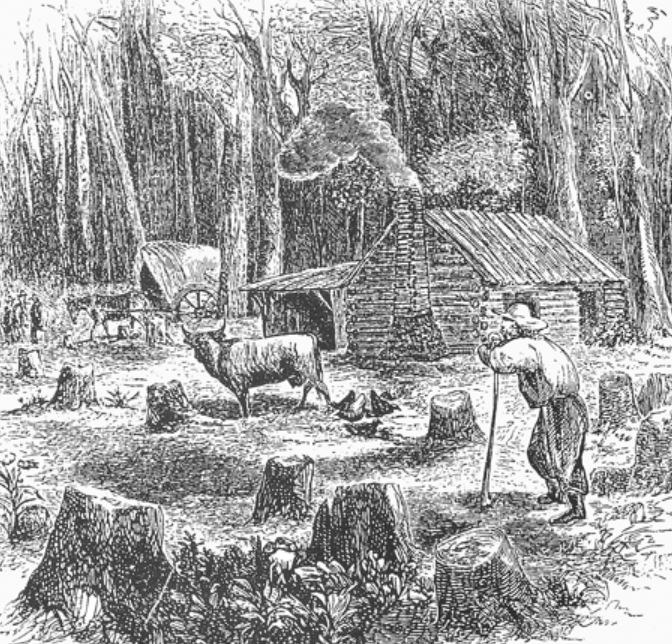

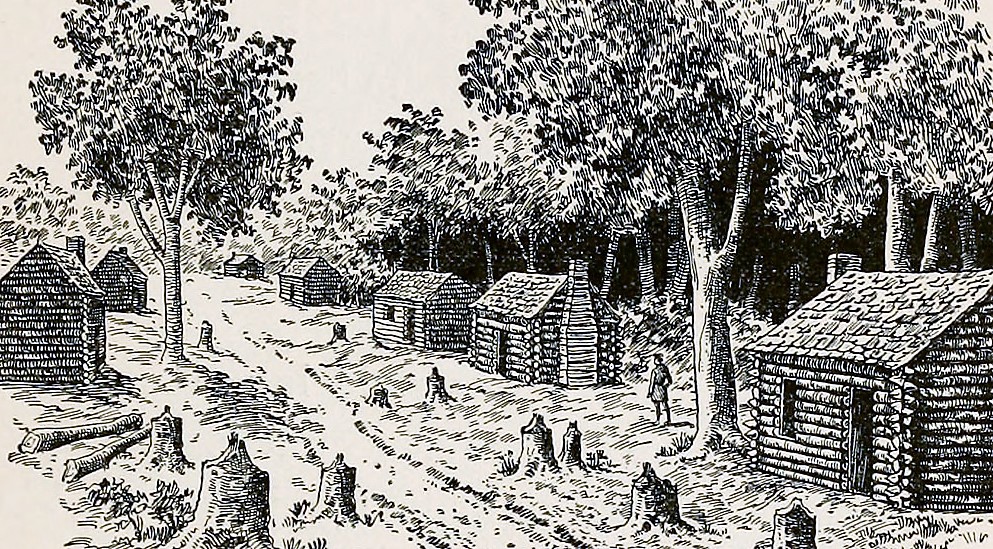

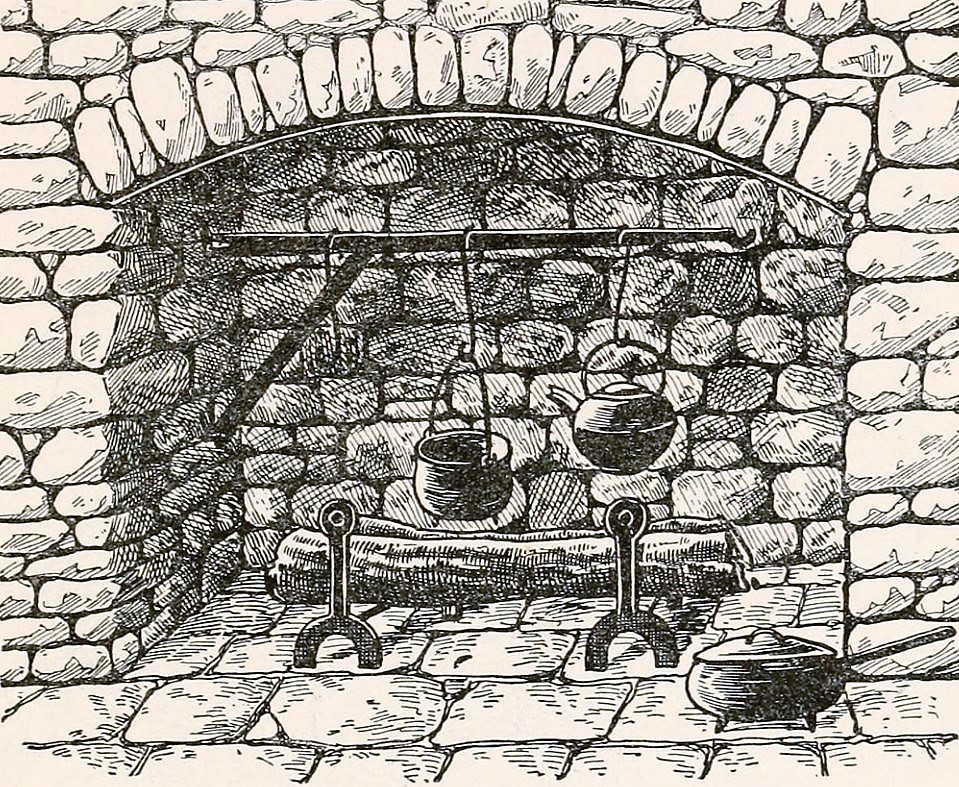

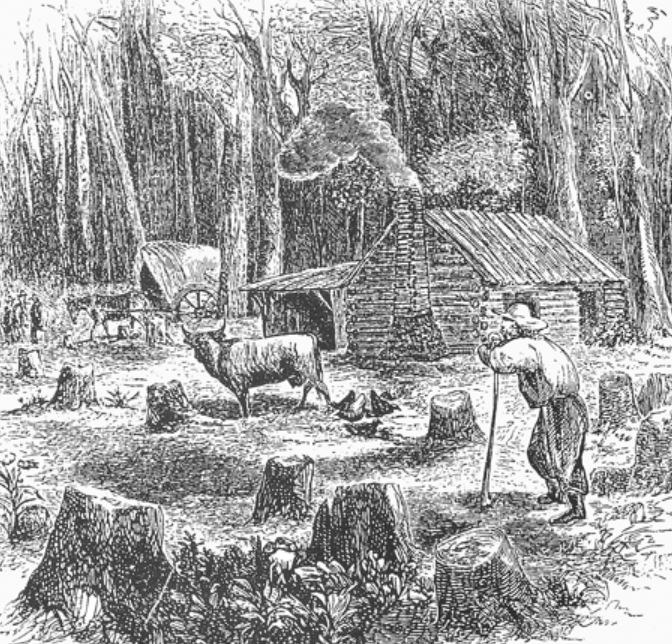

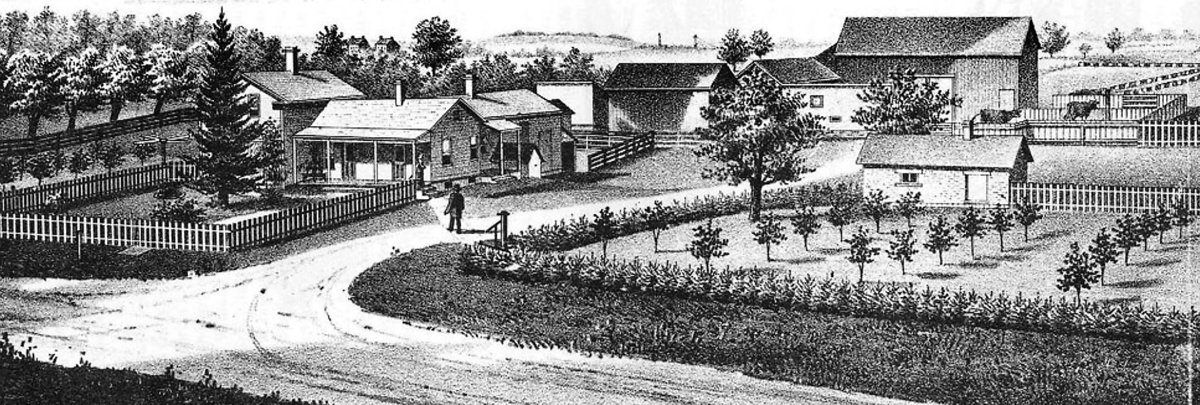

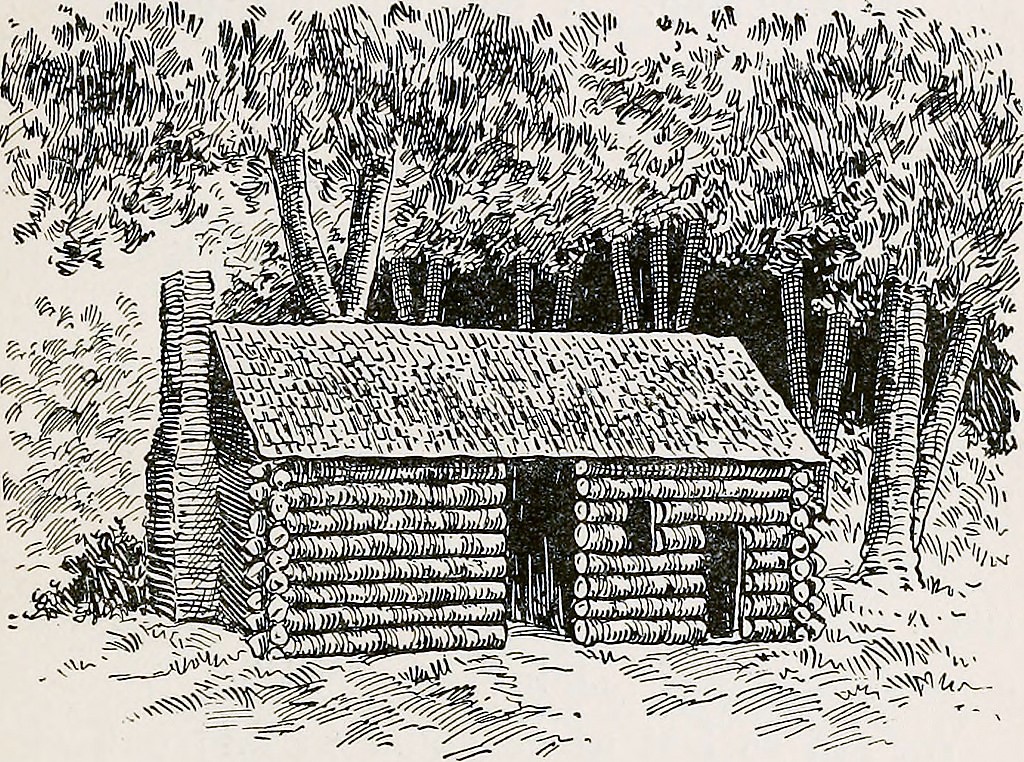

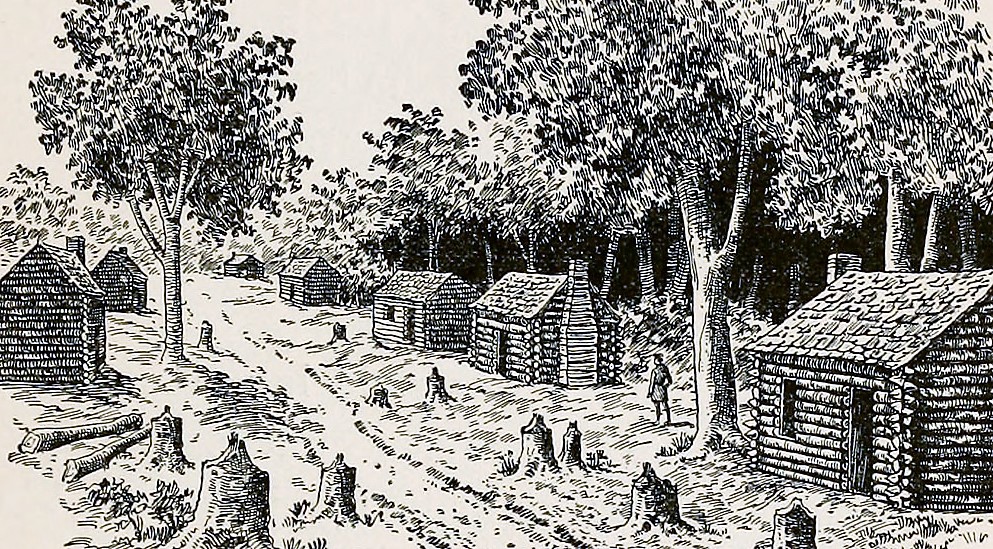

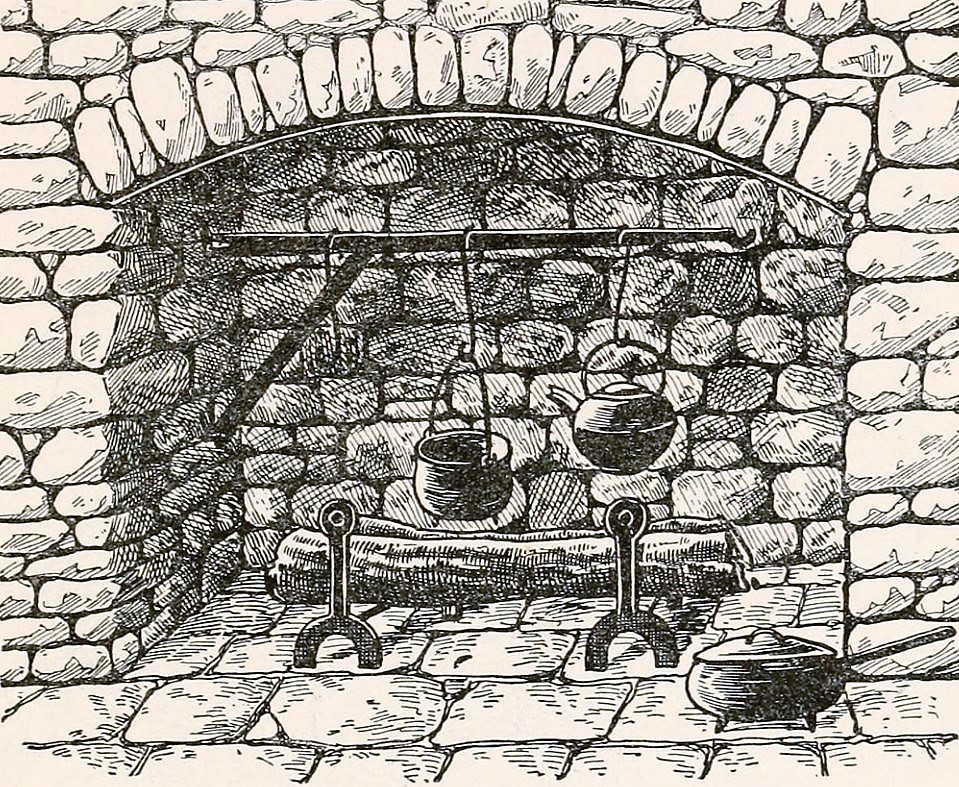

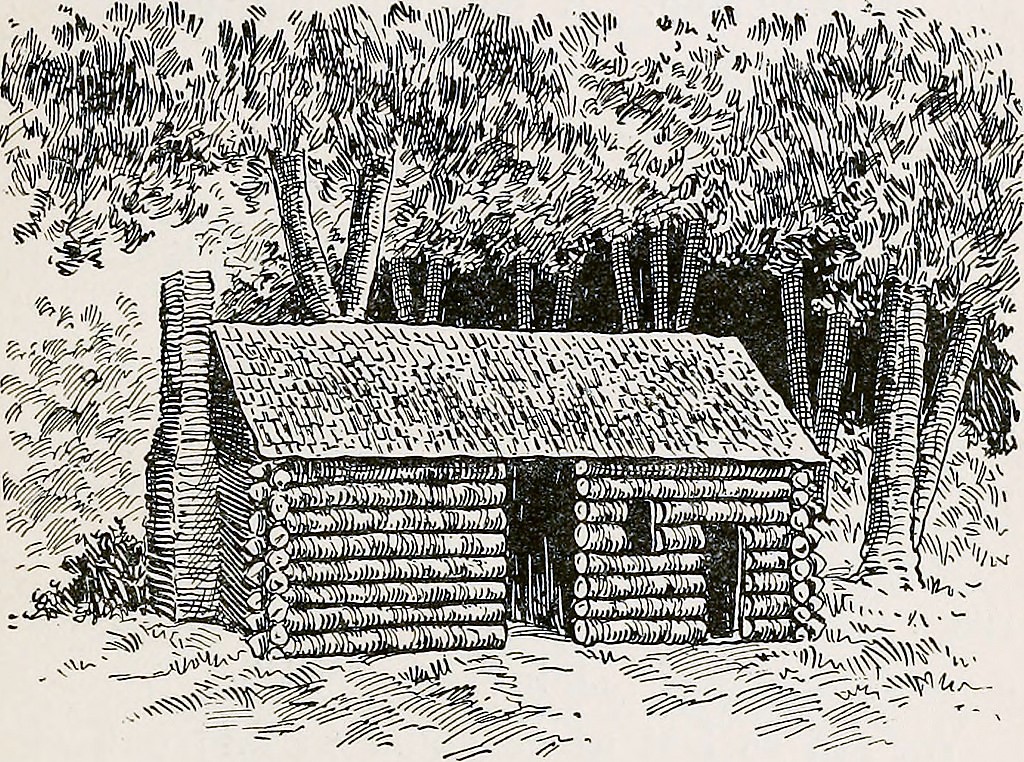

As successive families came on, they found shelter for a few weeks with those who had preceded them, until they could roll up a log house, roof it with “shakes” and cut an opening for a door. Then they would move into their new home and finish it at leisure. This finishing consisted in laying a floor of planks split from logs, puncheons as they were called; putting up a chimney in one end of the house, ordinarily of sticks plastered with clay, sometimes of stone, with a large open fireplace, generally made with a hearth and back, without jambs or mantel; adding at length a door, when there was leisure to go to Shupe’s Mill on Beaver creek, for a board; and a window of glass if it could be had - if not, oiled paper. A later stage in the operation consisted in “chinking” the cracks between the logs with pieces of wood on the inside, and plastering them without with clay mortar.

As leisure and prosperity followed, loose boards were laid above for a chamber floor, and in cases of unusual nicety and taste, the man devoted several evenings to hewing the logs on the sides within, and peeling the bark from the round joists overhead. Families unusually favored had rough stairs to the loft above, otherwise a ladder. An excavation below, entered through a trap in the floor, served as a cellar.

In rare cases, a family attained to the dignity of a sleeping room, separated from the common living apartment by a board partition; oftener chintz curtains, or sheets, or quilts, secured the privacy of the bed. These often disappeared as the wants of the family pressed, and the bed was left shelter-less.

The furniture of this primitive home was as simple as the domicile itself. The bedstead was made of round poles, shaved or peeled, the posts at the head rising above the bed and joined by a bar in place of a headboard. Elm bark often served in place of a cord. The trundle-bed was the same thing on a smaller scale. A table was extemporized from the cover of a box in which the family goods were brought from the east, while the box itself, with a shelf introduced, served as a cupboard for provisions. A shelf on the side of the room supported the crockery and tin ware, while a few stools, with now and then a back added, according to the mechanical skill or enterprise of the proprietor, served the place of chairs.

The furniture of this primitive home was as simple as the domicile itself. The bedstead was made of round poles, shaved or peeled, the posts at the head rising above the bed and joined by a bar in place of a headboard. Elm bark often served in place of a cord. The trundle-bed was the same thing on a smaller scale. A table was extemporized from the cover of a box in which the family goods were brought from the east, while the box itself, with a shelf introduced, served as a cupboard for provisions. A shelf on the side of the room supported the crockery and tin ware, while a few stools, with now and then a back added, according to the mechanical skill or enterprise of the proprietor, served the place of chairs.

This simple house, with its simpler furniture, furnished a home by no means uncomfortable where health, and hope, and kindly feeling were the light of it. The skeleton frame house of the pioneer of modern days, without paint, or ceiling, or plaster, or tree to shelter it, will by no means compare with the snug, well kinked, substantial log house of the early settlers.

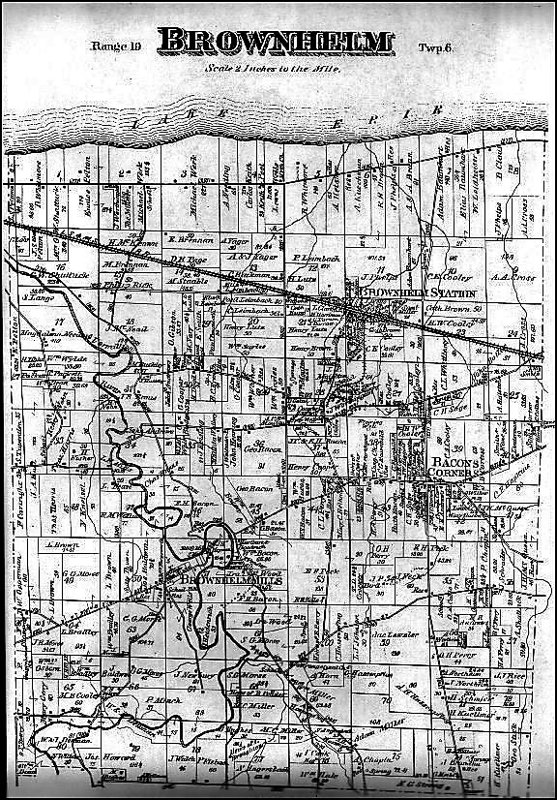

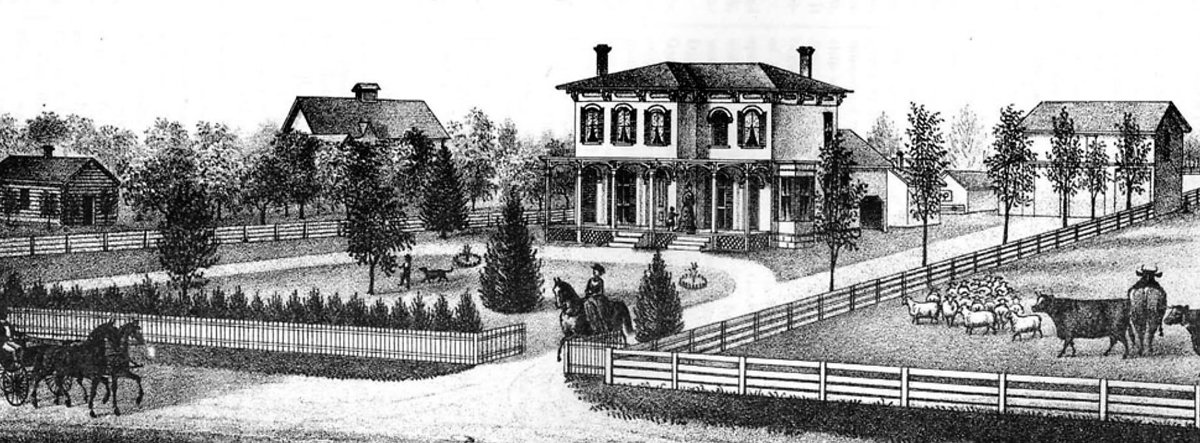

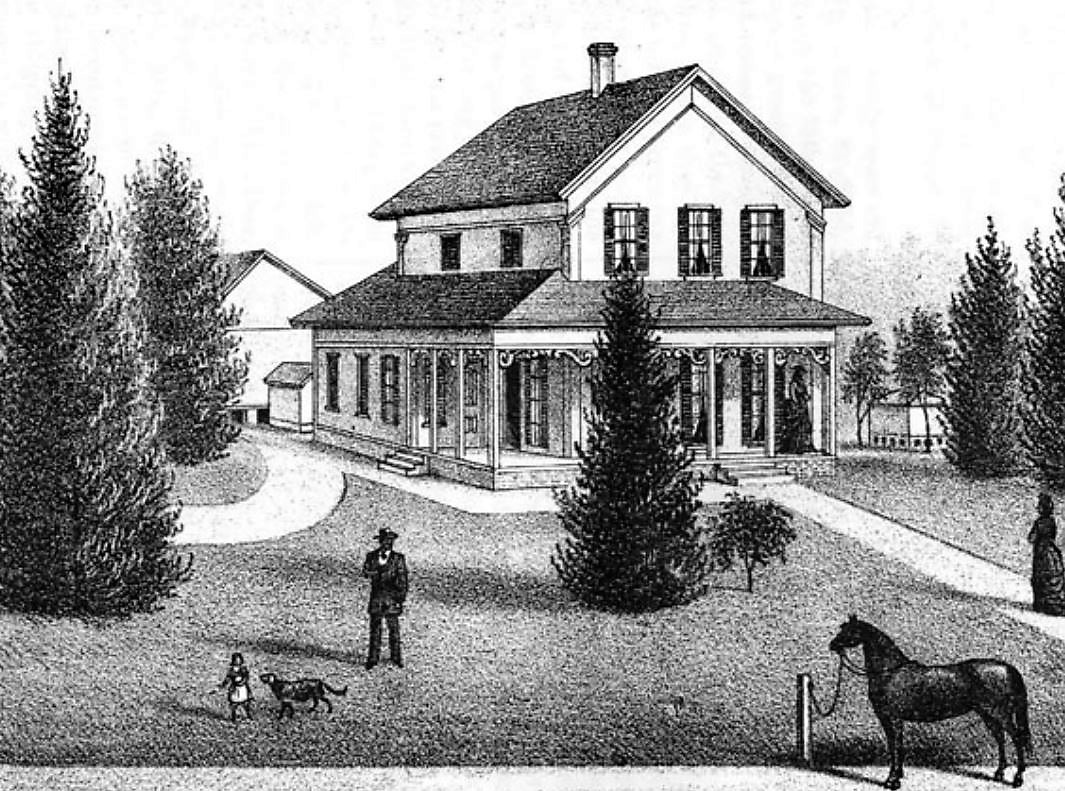

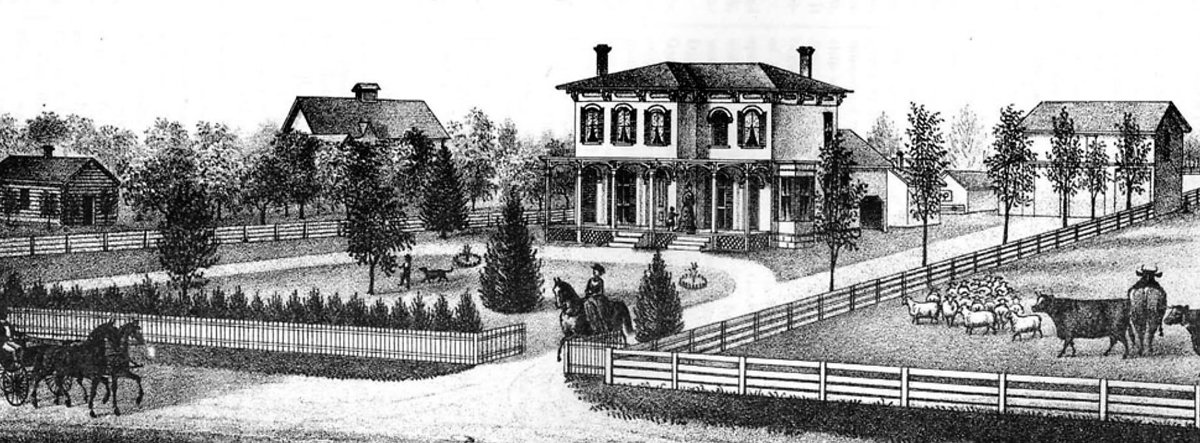

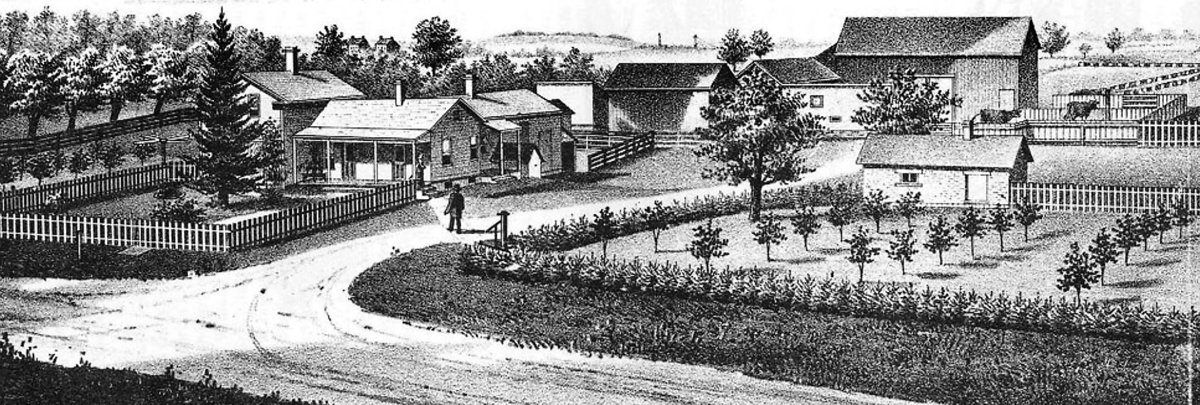

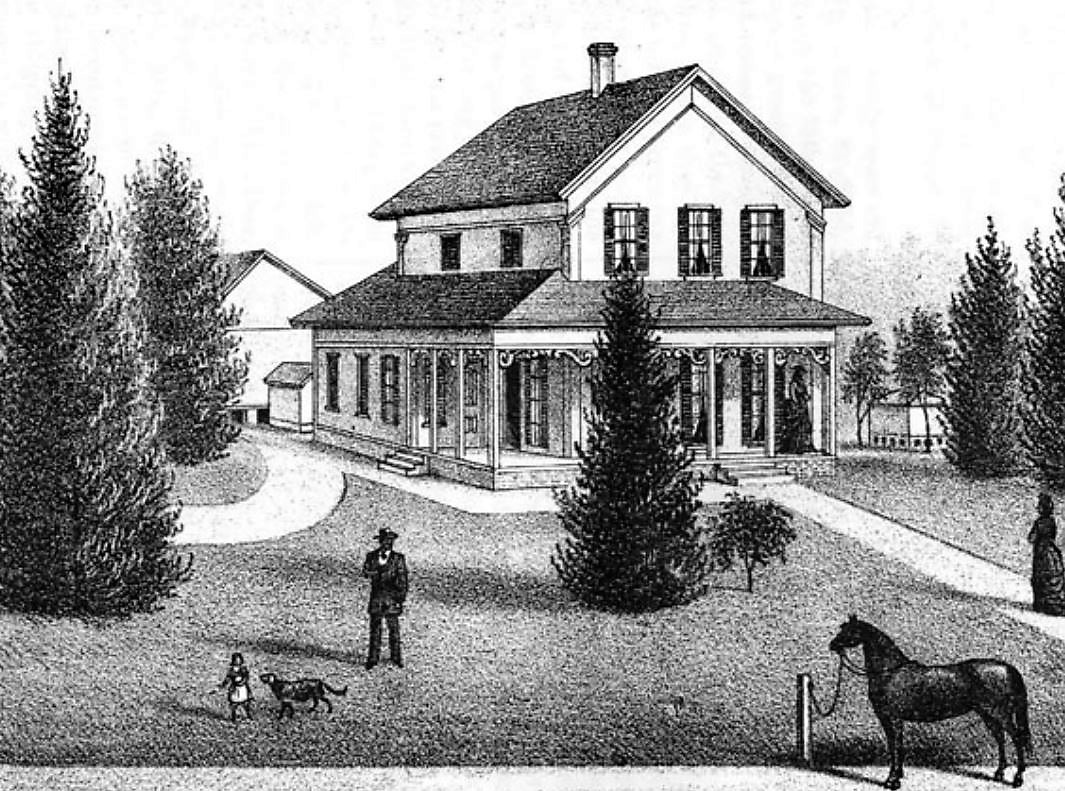

The first frame house in town was built by Benjamin Bacon, and the next by Dr. Betts. Mr. Bacon’s was the first painted one.

The first brick house in town, and indeed in the county, was built by Grandison Fairchild, in 1824. It was built with twenty thousand brick, at an aggregate cost of three hundred dollars. It later received some additions and improvements.

The first stylish house in town was Judge Brown’s, built in 1826, a grand affair in its day - a stately farm house.

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

The great drawback of the country, and at the same time its chief advantage, was the grand old forest with which the entire surface was covered, furnishing every variety of timber that could be needed in a new country, in quantities that seemed absolutely inexhaustible.

Along the ridges the chestnut prevailed, the trunk from two to four feet in diameter, and a hundred feet in height, furnishing the best fencing material that any new country was ever blessed with. The only discount on the chestnut was in the fact that the stump would remain full thirty years, an offense to the farmer, unless some strenuous means were used to eradicate it. The surest way was to undermine it, and bury it on the spot where it grew. The tree next in value for timber was the whitewood or tulip tree, of regal majesty, and second only to the white pine for finishing lumber, and for some uses superior to it. The oak and the hickory, in every variety and of magnificent proportions, were found everywhere; and on the lowlands and river bottoms, the black walnut, probably the most stately tree of Northern Ohio forests, inferior in magnificence only to the famous red wood of California. A single specimen was standing on the Vermillion river bottom which was said to measure fifteen feet in diameter above the swell of the roots. In the early years, this valuable fancy timber only ranked next to the chestnut, and there are barns and cowsheds in town roofed with clean black walnut boards, two feet and more in width.

With the first settlers, these magnificent forests were not held in high appreciation. They were esteemed usurpers of the soil, and the great endeavor was to exterminate them. Coming generations are not able to comprehend the labor involved in this enterprise, or the pluck that could accomplish it. A man was famous according as he lifted up axes upon the thick trees. No iron sinewed engine was at hand to take the brunt of the work. The pioneer himself, equipped only with his axe, a yoke of oxen and a log chain, had to attack, lay low and reduce to ashes the forests that overhung his farm. The men that accomplished this were sturdy in limb and strong in heart. A feeble race would have retired from the encounter.

The farmer of the present day, who has only to turn over the prairie sod, and wait for the harvest, can know little of the labor involved in settling a heavy-timbered country. Yet, if this had been a prairie country, its settlement must have been deferred full twenty years. The forests were a vast store house of material for building and fencing, and for fuel. The house in stern labor could accomplish everything. But for these forests each family would have required a capital of a thousand or two of dollars, and facilities for the transportation of lumber and other material would have been required, and a market where the products of the soil could be exchanged for these materials. The pioneer found his best friend in the forest, but the friendship was one of stem conditions, yielding its advantages only to the brave hearted.

It is a little sad to look back to the uncounted thousands of splendid trees of white wood, and oak, and ash, and hickory, and black walnut. and chestnut, which by dint of vast labor were reduced to ashes. But our case is not peculiar; at some such sacrifice every new country is settled. The divine wisdom that planned the continent, placed the prairies west of the forests, and the gold still farther on in the direction of the “march of empire.” Any other arrangement would have obstructed or greatly retarded the occupation of the country. The habit contracted in the clearing of the lands, the passion for destroying trees, has sometimes survived the necessity. The men who rejoiced over the fall of every tree are not likely to cherish with sufficient care the remnants of the grand old forests, or to replant on the grounds, cleared with so much labor, the trees necessary for shade, and ornament, and utility.

The gladdest sound of childhood was the crash of falling trees, and mother and children together rushed out of the cabin as each giant fell, to see how the area of vision was extended. Thus, slowly and with huge labor, the cleared circle expanded around each home. When ground was required for cultivation more rapidly than it could be thoroughly cleared, the plan of “girdling” or “deadening” was adopted, which killed the larger trees and left them standing. The falling limbs of the girdled trees destroyed the crops and sometimes the cattle, and often crushed the fences, and now and then the cabin itself; and a fire in a girdling on a windy autumn night was full of terror to a whole neighborhood. The loss of many a hay-stack, and burn, and house, was the price of the seeming advantage. Then, too, the final clearing away of the principal. The branchless timber, case hardened in the sun, was a more discouraging work than the original thorough clearing would have been. But these facts were only learned by experience, and so every settlement had its “girdling.”

It was a stern work, the clearing up and subduing of these beautiful farms, snatching meanwhile from among the countless stumps, by hasty culture, the support of the family, and in many cases the means of paying for the farm, or at least the interest on the purchase price. He was a fortunate man who brought from the east the price of his land. It many cases it made the difference between success and failure. It was very discouraging, after a struggle of years with hard work and sickness, to find the original debt increasing instead of diminishing; and it is not strange that here and there one sold his “improvements” for the means of conveying his family back to the eastern home, and retired from the conflict. The great majority stood bravely to the work, and achieved a satisfactory success.

Clothes & Shoes

Clothes & Shoes

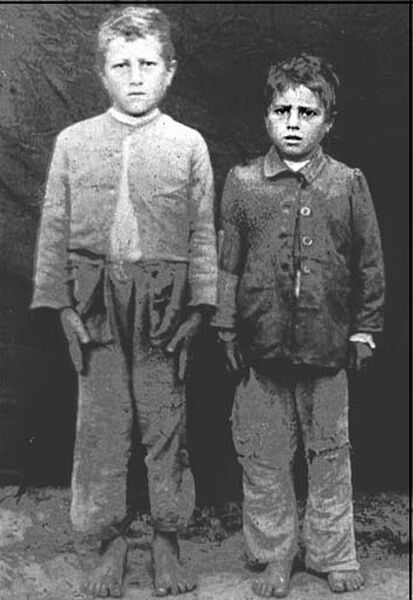

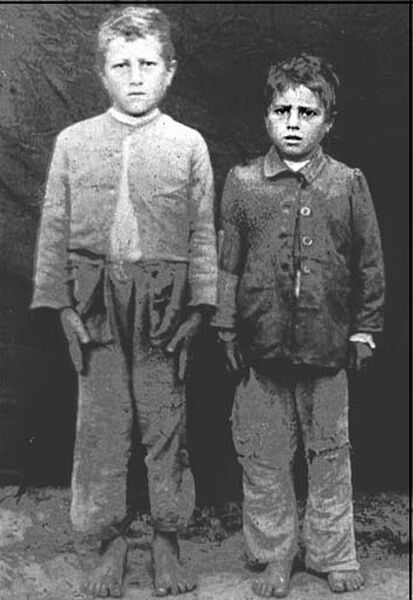

It is difficult for the young people of this day to appreciate the conditions of living in the new settlement. We need to recall the fact that northern Ohio was farther from the appliances of civilization than any portion of North America is today. The canal through the State of New York was not in existence, had scarcely been dreamed of. Western New York itself was mostly a bowling wilderness. The articles needed in the new country could not be brought from the far east except at ruinous cost, and for the produce of the new country the only market was that made by the wants of the occasional new families that joined the settlement. These generally brought a little money, which was soon divided among their neighbors. The families in general came well furnished with clothing, after the New England fashion; but a year or two of wear and tear in the woods, sadly reduced the store. The children did not stop growing in the woods, nor in those days did they cease to multiply and replenish the earth. The outgrown garments of the older children might serve for the younger, but where were the new garments for these older children to grow into? Flax could be raised, and summer linen of tow, and bleached linen, and copper as stripe, could be manufactured, when hands and health could be found to do it.

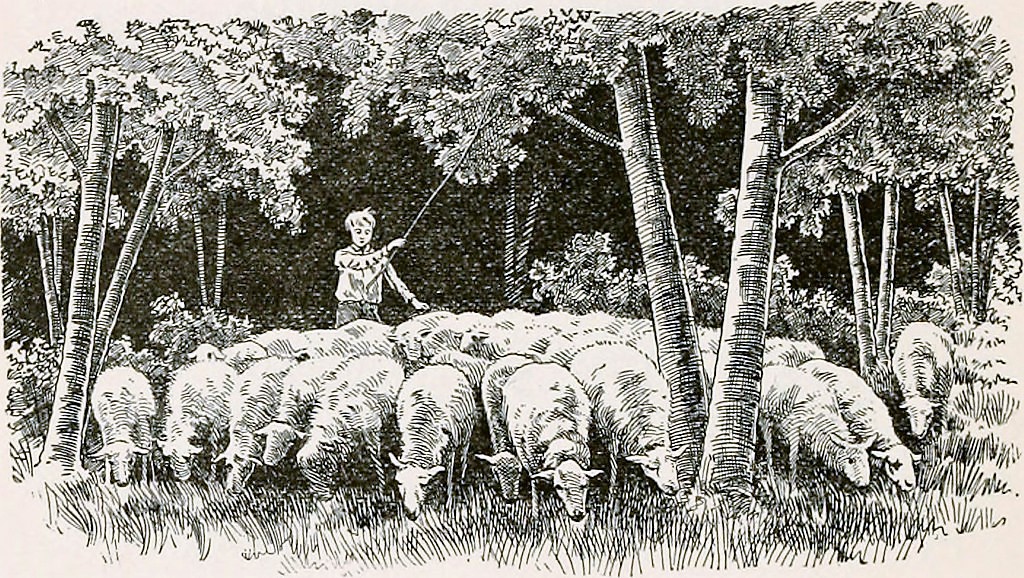

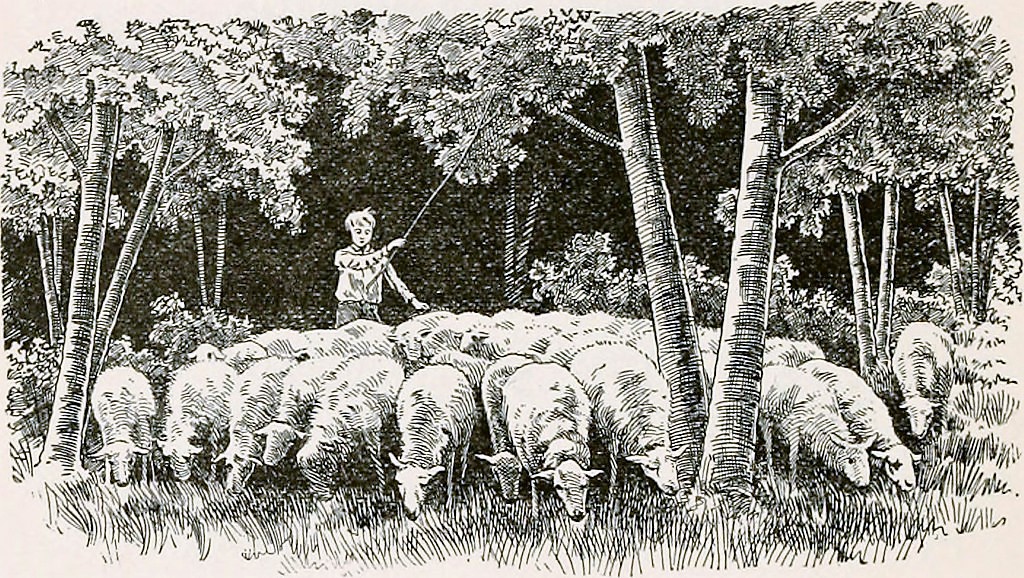

Every woman was a spinner, but only here and there was a weaver, and each family had to come in for its turn. The old garments often grew shabby before the piece which was to furnish the summer wear of the family could be put through the loom. In autumn the difficulty was increased. The material for winter clothing could not be extemporized in the new country. Sheep came in slowly. At first they were not safe from wolves, and afterwards the new lands proved unwholesome to them, and they died, often suddenly, without visible cause. But when wool could not be obtained, the process of manufacture was slow and the time uncertain. The spinning was a matter that could be managed; the weaving involved uncertainty, and then the web must be sent to the cloth-dresser and bide its time. It might come home long after thanksgiving, long after winter school began. Thus an unreasonable demand was made upon the summer clothing, a demand which it could but poorly answer. It was not rare to see a boy at school with his summer pants drawn over the remnants of his last winter’s wear, a combination which provided both for warmth and decency.

Some families dispensed altogether with the clothier’s services, and by the aid of a butternut dye gave their cloth a home dressing, avoiding the loss of time and the loss of surface by shrinkage - both important elements in the solution of the problem of clothing the boys. The undressed cloth was indeed rather light for winter, especially when the extravagance of underclothing, or of overcoats for the boys was never dreamed of ; but it was very much better than none. The various devices for making clothing served its purpose as long as possible, were in use, and some ingenious ones, unknown at the present day. Pantaloons were given a longer lease of life by facing the exposed portions with home-dressed deerskin. This served an admirable purpose, as long as there was enough of the original garment left to supply a skeleton; but at length the whole fabric would break down together, like the “wonderful one horse shay.” Garments made wholly of buckskin were sometimes attempted, but after a single wetting and drying, they were as uncomfortable as if made of sheet iron.

Some families dispensed altogether with the clothier’s services, and by the aid of a butternut dye gave their cloth a home dressing, avoiding the loss of time and the loss of surface by shrinkage - both important elements in the solution of the problem of clothing the boys. The undressed cloth was indeed rather light for winter, especially when the extravagance of underclothing, or of overcoats for the boys was never dreamed of ; but it was very much better than none. The various devices for making clothing served its purpose as long as possible, were in use, and some ingenious ones, unknown at the present day. Pantaloons were given a longer lease of life by facing the exposed portions with home-dressed deerskin. This served an admirable purpose, as long as there was enough of the original garment left to supply a skeleton; but at length the whole fabric would break down together, like the “wonderful one horse shay.” Garments made wholly of buckskin were sometimes attempted, but after a single wetting and drying, they were as uncomfortable as if made of sheet iron.

Leather was scarce, and shoes as a consequence. Here and there was a tannery, after a year or two; but where were the hides? Cattle were scarce, and too valuable to be sacrificed for such small comforts as shoes and, tallow candles, and fresh beef. If some disease had not appeared among them, now and then, the case would have been still worse. But in these simple times, a hide could not be tanned in a day. After long months the leather came, but shoemakers, proverbially slow, were indefinitely slower, when their outdoor work absorbed their energies, and they resorted to the bench only for spare evenings and rainy days. The boy must go for his shoes half score of times, and return with a promise for next week. The snow often came before the shoes, and then the shoes themselves would be a curiosity - made as they were indiscriminately from the skins of the hog, the dog, the deer, and the wolf.

Sometimes when the household store of clothing seemed nearly exhausted, and every garment had served its generation in a half dozen different forms, a box would come from the east brought by some family moving into the new country well charged with half worn garments and new cloth, and a stray string of dried apples to fill out a corner, enough to make glad the hearts of the recipients for a year. “Mother says we are rich now,” said three little boys to a neighbor’s children, whom they met in the road, after the arrival of a box from Stockbridge. “Well,” was the reply, “we are not rich, we are poor, and poor folks go to heaven, and rich folks don’t.” This was a new-view of the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, and the boys went home quite crest-fallen. It relieved this experience of poverty that all shared in it. Many wants are merely relative. We need good things because our neighbors have them. But in those days, there were few contrasts to disturb even the poorest. Still, without any reference to others, there is some slight discomfort to a boy in calling at a neighbor’s house in such a plight that he cannot safely turn his back to the people as he leaves the house; or in crossing the meadow on a frosty morning with bare feet, stopping now and then to warm them on a stone not so cold as the grass.

Food

Food

In the matter of necessary food, the new country was more generous. The soil yielded abundantly when once brought under cultivation, furnishing the substantials of life. The material of bread was abundant, but in a dry season, the wheat could not be ground. Brown’s mill, on the Vermillion, was the first to fail; then Shupe’s on Bearer creek, Stair’s at Birmingham, and last Ely’s at Elyria. The grists were ground in the order of their reception, and sometimes a family was obliged to wait weeks for its turn, as the water was sufficient only for an hour’s work in a day; and sometimes the mill rested for days in succession. Then it was no small enterprise to go to Elyria to mill. There was a time when there were not a half dozen horses in town. Mr. Peck had a span, Mr. Bacon one, and Judge Brown a span. These horses were freely lent, but they could not meet the requirements of the entire settlement, when the mill was a dozen miles away, and still be of any use to their owners. When one went to mill with a team, he was expected to carry the grists of his neighbors, or bring them home, if he found them ground. When the mills were at rest, it was allowable to borrow as long as there was any flour in the neighborhood, and when it failed, they enjoyed a week’s variety of “jointed corn” or pounded wheat. There was a little peril to young hands in this work of “jointing” corn, and many a thumb bared marks as the fossil bird tracks of the Connecticut sand stone.

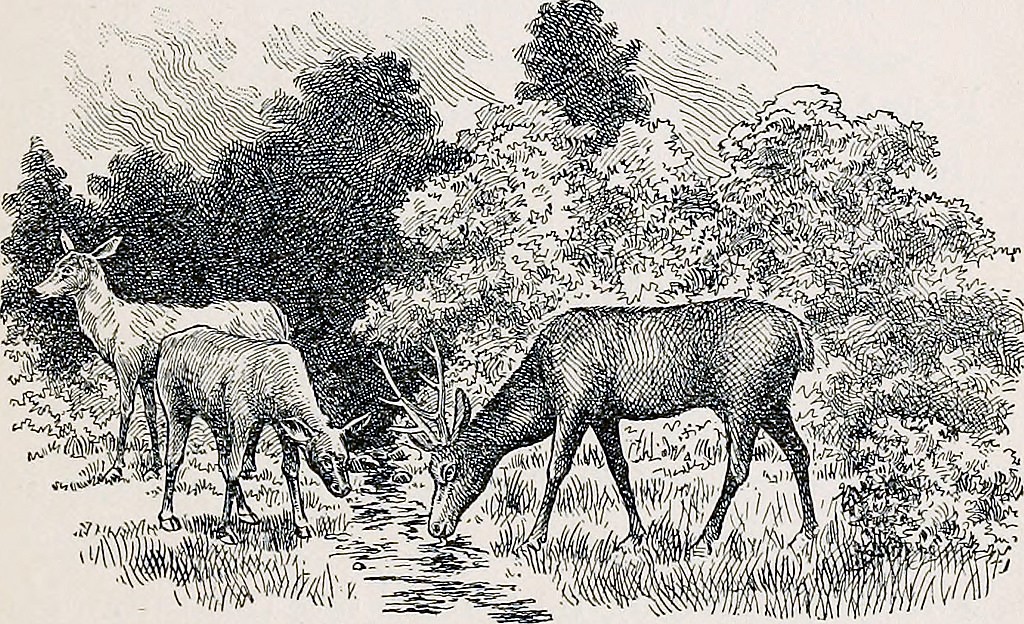

Pork was the staple article in flesh, an ox or a cow being too valuable to slaughter. There was venison and other wild game - so plenty at times as to become a drug. Such meats were likely to be regarded as fancy adornments of a bill of fare, not satisfactory as an every day reliance. When an original Brownhelmer went to the city, he was not likely to call for venison, unless to recall the early experience, as the people of Israel used unleavened bread and bitter herbs at the Passover. He had done his duty in that line of eating. Roasted raccoon and baked opossum were never popular.

The supply of fruits was not abundant. Three years sufficed to bring the peach into hearing from the stone; hence, this was the earliest cultivated fruit. The diseases and insects that ruin the peach tree were then unknown. A wagon load of the finest peaches could be had for the gathering. Peach cider was attempted in various parts of the town, before the advent of teetotalism, but the cause of temperance never suffered from it. Apples and pears came on very slowly. The plan of grafting was not much in use, and the virgin soil which stimulated the growth of wood, was not favorable to early fruitage. Now and then a stray apple reached them from the orchard of Horatio Perry, or of Judge Ruggles in Vermillion. And what a flavor there was in that slice from a pippin, brought by Mr. Alverson, all the way from Stockbridge, in his knapsack! The first pear that the boy tasted he was not allowed to see. He was told to shut his eyes and open his mouth, and a bit of the delicious mystery was placed upon his tongue.

The supply of fruits was not abundant. Three years sufficed to bring the peach into hearing from the stone; hence, this was the earliest cultivated fruit. The diseases and insects that ruin the peach tree were then unknown. A wagon load of the finest peaches could be had for the gathering. Peach cider was attempted in various parts of the town, before the advent of teetotalism, but the cause of temperance never suffered from it. Apples and pears came on very slowly. The plan of grafting was not much in use, and the virgin soil which stimulated the growth of wood, was not favorable to early fruitage. Now and then a stray apple reached them from the orchard of Horatio Perry, or of Judge Ruggles in Vermillion. And what a flavor there was in that slice from a pippin, brought by Mr. Alverson, all the way from Stockbridge, in his knapsack! The first pear that the boy tasted he was not allowed to see. He was told to shut his eyes and open his mouth, and a bit of the delicious mystery was placed upon his tongue.

Sugar could be obtained from the maple then, but the maple tree was not abundant in the township. Many farms were entirely destitute of it, and few families made sugar enough for the year’s supply. It was not a rare thing for a family to be without sugar for months in succession. Honey and pumpkin molasses were used as substitutes for sweetening tea and making gingerbread, not quite equal to refined sugar; but they served to keep alive the idea of sweetness. Genuine tea, old or young hyson, was regarded as a necessary of life, and no well conditioned family could be found without it. But it would astonish a modern housekeeper to hear how small a quantity would meet the necessity. Children never needed it; it was not good for them; and a pound would supply a family for a year. Tea must have been a different thing in those times. A single teaspoonful, well steeped, would furnish sociability to a half dozen ladies of an afternoon; and the same pot, refilled with water, would charm away the weariness of the men folks, when they returned from their work. A cargo of such tea, in these days, would make the fortune of the importer. Store coffee was essentially unknown, and therefore not needed.

The table furniture was simple, and the frugal habits of New England on this point, favored the condition of the people. The food was placed in a common dish in the middle of the table, the potato mashed and seasoned to the taste, and the meat cut in mouthfuls ready for appropriation. A knife and fork at each place sufficed, or even one of them would do for the children. A drinking-cup or tumbler at each end of the table was ample. If bread and milk was the bill of fare, a single bowl and spoon could do duty for the entire family, going down from the oldest to the youngest. This may seem like imagination— it is simple fact. Commonly a tin basin or pewter porringer went around among the younger children; but as they grew older they preferred to wait, for the sake of using the crockery ware.

In those dark-walled log cabins, a single tallow candle would not seem so afford superfluous light of a winter evening; but only favored families could indulge the luxury. The candle was lighted when visitors came. At other times the bright wood fire was the chief reliance, and for sewing or reading a nicked tea saucer filled with hog’s fat, and a wick of twisted rag projecting over the edge. This was the classic lamp of the log cabin, open to accident indeed, but a dash of grease on the puncheon floor was an immaterial circumstance. Two dipped candles furnished the light for an evening meeting, the hour for which was very properly designated as “early candle lighting.”

Black Salts

Black Salts

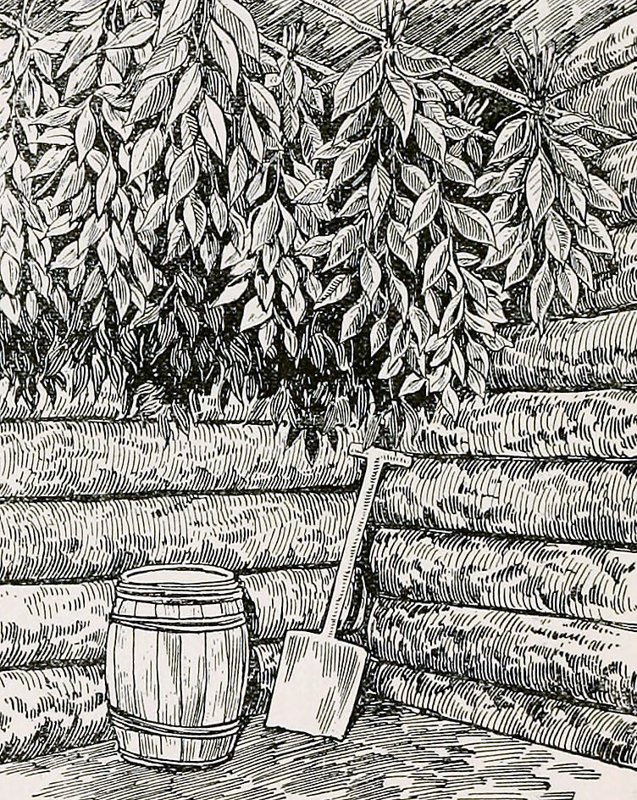

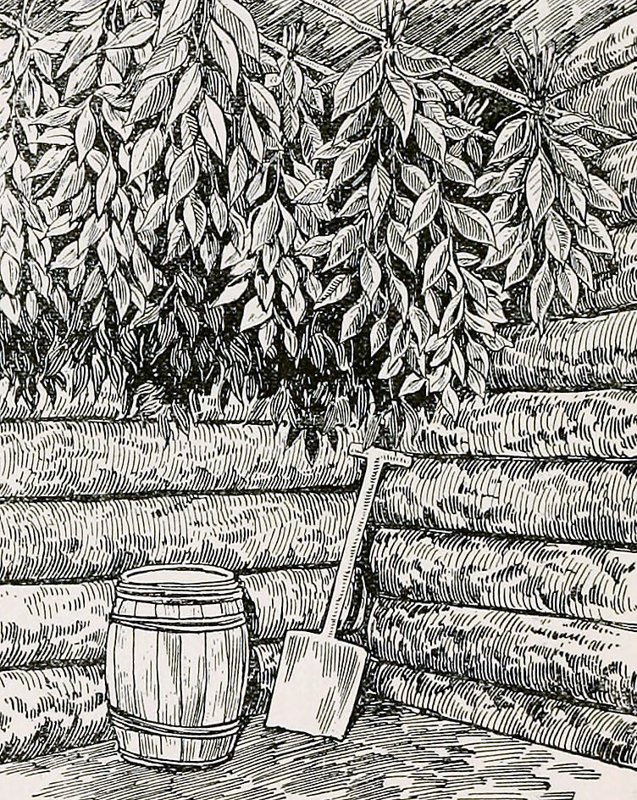

The outdoor life of the early settlers presented some peculiar features. The chief item of farm work was clearing land. The first, and in some respects the most valuable products of this labor, was derived from the ashes of the burnt forests. Black salts, or potash, concentrated much value in a small bulk and hence would bear transportation to a distant market. For years it was the only article of farm produce which would bring money.

Some trader at the mouth of Black river, or at Elyria, would pay one-third cash for this article, and the balance in goods. Thus the farmer could raise the money to pay his taxes, and a little more for tea and cotton cloth. which were always cash articles.

Wheat and corn would not sell for cash, except occasionally a little to an immigrant, until about the time of the completion of the Erie canal. It was the height of prosperity when at length white flint corn came to sell at eighteen cents a bushel, and white army beans at thirty to fifty cents. From that day they were “out of the woods.”

Wild Animals

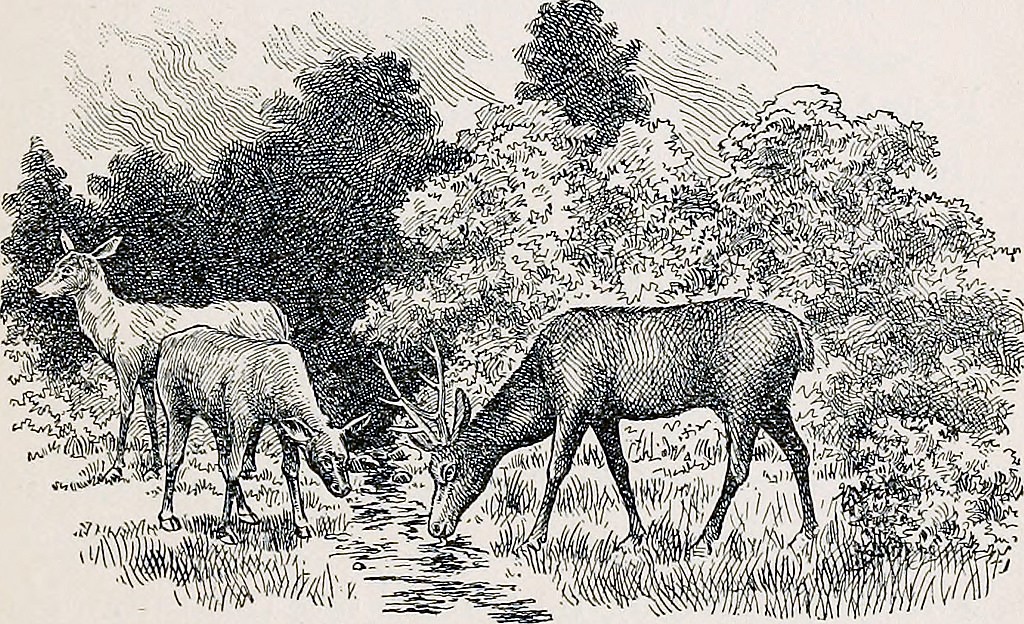

Wild Animals

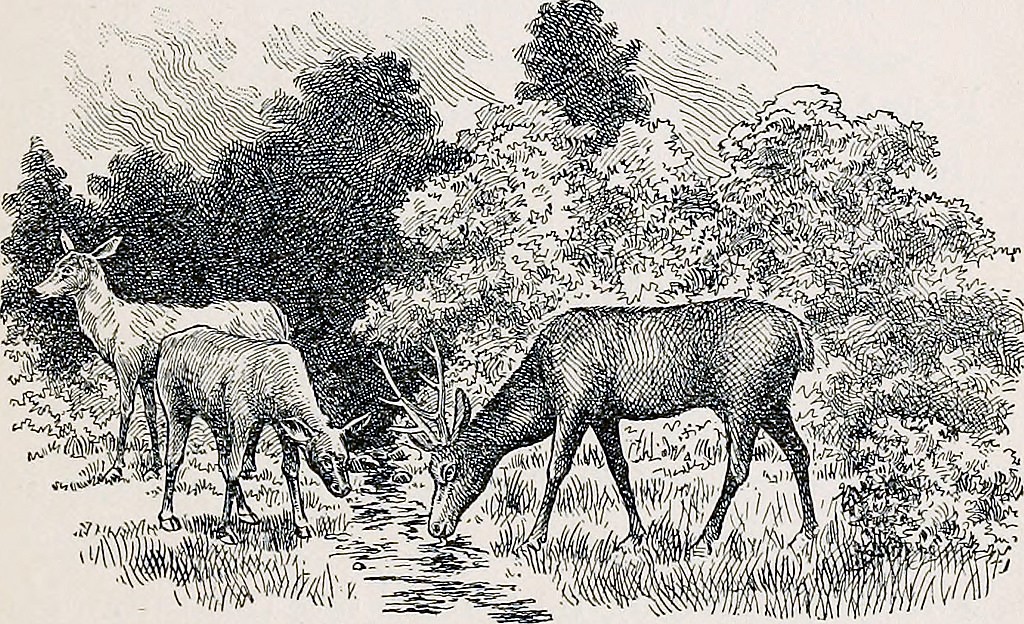

One of the features of early life here was familiarity with the wild animals that had possession of the country. The howl of the wolf at night was as familiar as the whip-poor-will’s song - not the small prairie wolf so well known at the west, but the powerful wolf of the forest, the black and the gray. They passed in droves by the dwellings at night, sometimes when the new comers had only a blanket suspended in the opening for the door. Sometimes they crowded upon the footsteps of a belated settler, passing from one part of the settlement to another, The boy crossing the pasture on a winter morning would often see the blind track of a wolf that had loped across the night before. If he had forgotten to bring in his sheep at evening, he might find them scattered and torn in the morning. A dog that ventured from the house at night, sometimes came in with wounds more honorable than comfortable. The wolf was a shy animal, seldom showing itself by day light.

Probably not one in a dozen of the early inhabitants ever saw a wolf in the forest; yet these animals roamed the woods around Brownhelm for years. Mr. Solomon Whittlesey once snatched his calf from the jaws of a wolf, at night, with many pairs of hungry eyes gleaming upon him through the darkness. In 1827, the county commissioners offered a bounty for wolf scalps - three dollars for a full-grown wolf, and half the sum for a whelp of three months. Whether any drafts were ever made upon the treasury does not appear.

Now and then a wolf was taken in a trap or shot by a hunter. Probably less than a half-dozen were ever killed in the township. About the winter of 1827-28, wolf hunts were organized in the region on a grand scale, conducted by surrounding it tract of country several miles in extent, with a line of men within sight of each other at the start, and approaching each other as they moved toward the center. The first of these hunts centered in Henrietta, and resulted in bagging large quantities of game, but never a wolf. A single wolf made his appearance at the center, and was snapped at and shot at by many a rifle, but he got off with a whole skin.

The sport involved danger from the cross-shooting as the line drew near the center, and Park Harris, of Amherst, mounted on a horse, received a shot in the ankle. To avoid this danger, the next hunt centered on the river hollow, about the mill in Brownhelm, but the scale on which it was arranged was too grand to be carried out. The lilies were too extended and broke in many places, resulting in gathering upon the flat a small herd of deer and a solitary fox, barely furnishing an occasion for the hundreds of huntsmen above to discharge their pieces, as the frightened animals escaped into the woods up the river. It was an utterly fruitless chase. A more exciting chase was the slave-hunt of a later day, in which the people bewildered and foiled the kidnappers.

Bears were less numerous than wolves, but they were perhaps more often seen. One was shot by Solomon Whittlesey, from the ridge, a little east of the burying ground. One of the trials of childish courage was to pass the tree against which tradition said that he rested his rifle in the shot. Another dangerous tree was the large basswood that leaned over the brook, a little to the south-east of Harvey Perry’s orchard. Mrs. Fairchild, going over the ridge to bring a pail of water from the spring, once drove a large black animal before her which she thought a dog until he scrambled up that tree when she returned home without the water. The tree stood close by the track that led to Mr. Peck’s, and it was a test of pluck for a child to pass that tree just as the evening began to darken. One day, one of a half dozen sheep was missing. In looking for the lost animal, a place was found where it seemed to have been dragged over the fence where a bear had made his feast, leaving the wool scattered about and a few large bones. The tracks were still fresh in the mud.

Such occurrences gave a smack of adventure to child life in the new country, and it was a matter of every day consultation among the boys, what were the habits of the various animals supposed to be dangerous, such as the wolf, the bear, the wild cat, and the panther, and by what tactics it was safest to meet them. Similar discussions were had in reference to the Indians, who had required a bad reputation during the war, then recent, with England. The prevailing opinion was, that any fear exhibited towards an Indian, or a wild beast, put one at a great disadvantage.

Deer were far more plenty than cattle, and the sight of them was an everyday occurrence. A good marks man would sometimes shoot one from his door. The same was true of wild turkeys. Raccoons worked mischief in the unripe corn, and a favorite sport of the boys was “coon hunting” at night, the time when the creature visited the corn. A dog traversed the cornfield to start the game, and the boys ran at the first bark of the dog, to be in at the death. When the animal took to a tree, it was cut down, or a fire was built and a guard set to keep him until morning, when he was brought down by a shot. The motive for the hunt was three-fold - the sport, the protection of the corn, and the value of the skin; the raccoon being a furred animal.

The greatest speculation in this line of which the town can boast, was made by Job Smith, “a man of some note.” He is said to have bought a quantity of goods of a New York dealer, promising to pay “five hundred coon skins taken as they run,” naturally meaning an average lot. The dealer, after waiting a reasonable time for his fur, came on to investigate, and inquired of his debtor when the skins would be delivered. “Why,” said Mr. Smith, “you were to take them as they run; the woods are full of them; take them when you please.” The moral of the story would not be complete with out stating that the same Job Smith was afterwards arrested as a manufacturer of counterfeit coin.

Thrifty men pursued the business of hunting as a pastime. The only man in town, perhaps, to whom it afforded profitable business, in any sense, was Solomon Whittlesey. Other professional hunters were shiftless men, to whom hunting was a mere passion, having something of the attractions of gambling. Mr. Whittlesey did not neglect his farm, but he knew every haunt and path of the deer and the turkey, and was often on their track by day and by night. He reported the killing of one bear, two wolves, twenty wild cats, about one hundred fifty deer, and smaller game too numerous to specify. One branch of his business was bee hunting, a pursuit which required a keen eye, good judgment and practice. The method of the hunt was to raise an odor in the forest, by placing honey comb on a hot stone, and in the vicinity another piece of comb charged with honey. The bees were attracted by the smell, and having gorged themselves with the honey, they took a bee-line for their tree. This line the hunter observed and marked by two or more trees in range. He then took another station, not on this line, and went through the same operation. Those two lines, if fortunately selected, would converge upon the bee tree, and could be followed out by a pocket compass. The tree, when found, was marked by the hunter with his initials, and could be cut down at the proper time.

Another form of the sport of hunting was even more classic, the hunting of the wild boar. For many years there was an unbroken forest, two miles in breadth, running through the township, between the North Ridge and the lake shore farms. This forest became the haunt of fugitive hogs that fed on the abundant mast, or, in Yankee phrase, “shack,” which the forest yielded. These animals were bred in the forest, and in the third generation became as fierce as the wild boar of the European forest. The animal in this condition was about as worthless, for domestic purposes, as a wolf, as gaunt and as savage. Still it was customary, in the fall and early winter, to organize hunts for reclaiming some valuable animal that had become thus degenerate. The hunt was exciting and dangerous. The genuine wild boar, exasperated by dogs, was the most terrible creature in the forest. His onset was too sudden and headlong to be avoided or turned aside, and the snap of his tusks, as he sharpened them in his fury, was somewhat terrible. Two at least of the young men, Walter Crocker and Truman Tryon, were thrown down and badly rent in such encounters, and others had narrow escapes.

The principal fishing ground of the early years was the “flood wood” of the Vermillion. The lake fishing is a modern discovery. It was not known that the lake contained fish that were accessible. Other sports and recreations were few and simple, most of them presenting the utilitarian element. There were logging bees to help a man who had been sick or unfortunate, raisings to put up a log cabin or barn, and militia trainings, which were entered into earnestly by men who had smelt powder in the recent war.

The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio

The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio

Children from every part of the town attended. There was no public school fund in those times and the teacher received his compensation in work in his chopping the next spring day, being distributed among the families according to the number of children attending the school. For years afterwards teachers received their pay in farm produce.

Children from every part of the town attended. There was no public school fund in those times and the teacher received his compensation in work in his chopping the next spring day, being distributed among the families according to the number of children attending the school. For years afterwards teachers received their pay in farm produce. Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio The furniture of this primitive home was as simple as the domicile itself. The bedstead was made of round poles, shaved or peeled, the posts at the head rising above the bed and joined by a bar in place of a headboard. Elm bark often served in place of a cord. The trundle-bed was the same thing on a smaller scale. A table was extemporized from the cover of a box in which the family goods were brought from the east, while the box itself, with a shelf introduced, served as a cupboard for provisions. A shelf on the side of the room supported the crockery and tin ware, while a few stools, with now and then a back added, according to the mechanical skill or enterprise of the proprietor, served the place of chairs.

The furniture of this primitive home was as simple as the domicile itself. The bedstead was made of round poles, shaved or peeled, the posts at the head rising above the bed and joined by a bar in place of a headboard. Elm bark often served in place of a cord. The trundle-bed was the same thing on a smaller scale. A table was extemporized from the cover of a box in which the family goods were brought from the east, while the box itself, with a shelf introduced, served as a cupboard for provisions. A shelf on the side of the room supported the crockery and tin ware, while a few stools, with now and then a back added, according to the mechanical skill or enterprise of the proprietor, served the place of chairs. The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm Clothes & Shoes

Clothes & Shoes Some families dispensed altogether with the clothier’s services, and by the aid of a butternut dye gave their cloth a home dressing, avoiding the loss of time and the loss of surface by shrinkage - both important elements in the solution of the problem of clothing the boys. The undressed cloth was indeed rather light for winter, especially when the extravagance of underclothing, or of overcoats for the boys was never dreamed of ; but it was very much better than none. The various devices for making clothing served its purpose as long as possible, were in use, and some ingenious ones, unknown at the present day. Pantaloons were given a longer lease of life by facing the exposed portions with home-dressed deerskin. This served an admirable purpose, as long as there was enough of the original garment left to supply a skeleton; but at length the whole fabric would break down together, like the “wonderful one horse shay.” Garments made wholly of buckskin were sometimes attempted, but after a single wetting and drying, they were as uncomfortable as if made of sheet iron.

Some families dispensed altogether with the clothier’s services, and by the aid of a butternut dye gave their cloth a home dressing, avoiding the loss of time and the loss of surface by shrinkage - both important elements in the solution of the problem of clothing the boys. The undressed cloth was indeed rather light for winter, especially when the extravagance of underclothing, or of overcoats for the boys was never dreamed of ; but it was very much better than none. The various devices for making clothing served its purpose as long as possible, were in use, and some ingenious ones, unknown at the present day. Pantaloons were given a longer lease of life by facing the exposed portions with home-dressed deerskin. This served an admirable purpose, as long as there was enough of the original garment left to supply a skeleton; but at length the whole fabric would break down together, like the “wonderful one horse shay.” Garments made wholly of buckskin were sometimes attempted, but after a single wetting and drying, they were as uncomfortable as if made of sheet iron. Food

Food Black Salts

Black Salts Wild Animals

Wild Animals Early Farm Life Of Brownhelm Township Ohio

Early Farm Life Of Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Education In Brownhelm Ohio

Early Education In Brownhelm Ohio In 1824 the "Yellow School House" was built a few feet west of the log one and the boys had the exquisite pleasure of rolling the old house down the hill. This yellow school house was an elegant one in its day, painted throughout and plastered. It was no ordinary school house, but a genuine academy furnished with unusual apparatus globes and wall maps, and pantograph and tables for map drawing and painting. This was the first attempt in the county, and indeed in a much wider region, at a school of anything more than a local character. It prospered for two or three years, attracting young ladies in the summer from all the older settlements within a distance of twenty miles - Milan, Norwalk, Florence, Elyria, Shelfield etc.

In 1824 the "Yellow School House" was built a few feet west of the log one and the boys had the exquisite pleasure of rolling the old house down the hill. This yellow school house was an elegant one in its day, painted throughout and plastered. It was no ordinary school house, but a genuine academy furnished with unusual apparatus globes and wall maps, and pantograph and tables for map drawing and painting. This was the first attempt in the county, and indeed in a much wider region, at a school of anything more than a local character. It prospered for two or three years, attracting young ladies in the summer from all the older settlements within a distance of twenty miles - Milan, Norwalk, Florence, Elyria, Shelfield etc. Early Religion In Brownhelm Township Ohio

Early Religion In Brownhelm Township Ohio Brownhelm Township Ohio: The Firsts

Brownhelm Township Ohio: The Firsts Brownhelm Ohio Fourth Of July

Brownhelm Ohio Fourth Of July Difficulties & Compensations In Early Brownhelm Township

Difficulties & Compensations In Early Brownhelm Township Township & Village Unite

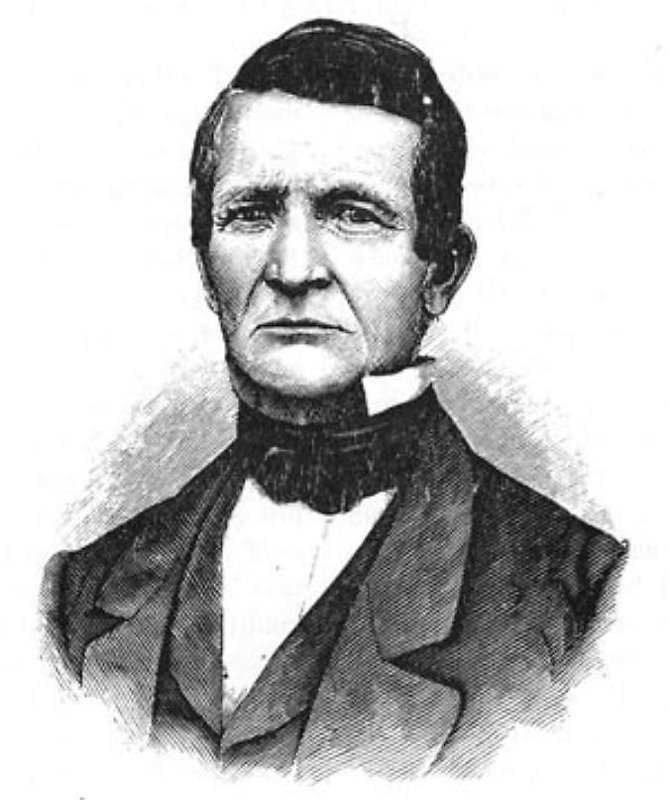

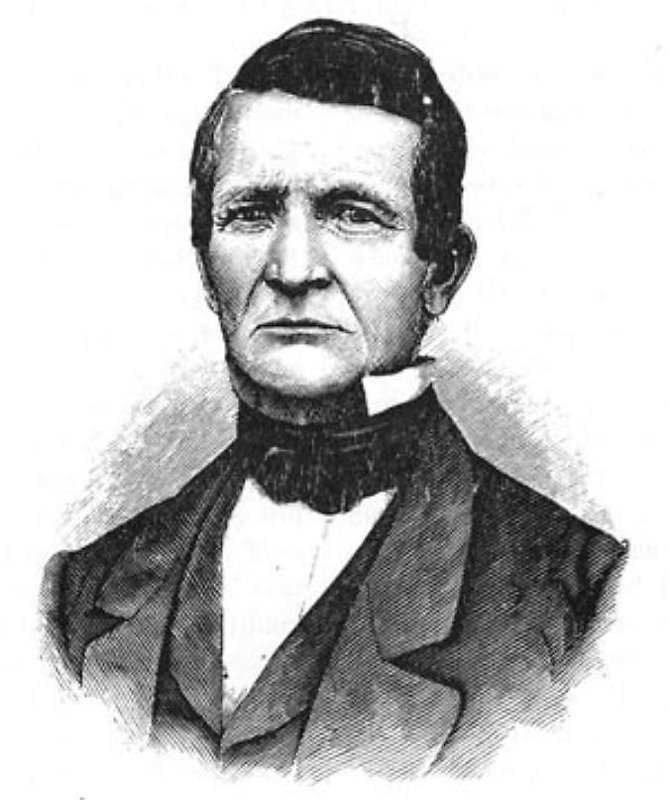

Township & Village Unite John Mercer Langston

John Mercer Langston

The Haunting History of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow

The Haunting History of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow The Real Story of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow

The Real Story of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow Shortly before the investigation, in 1908, a disaster took place in the town of Collinwood, some forty miles east of Vermilion. 176 elementary school students were burned or trampled to death when they became trapped in a stampede situation and couldn’t escape a fire that was consuming their school. The children began descending down the stairs to the exit after the fire alarm was sounded, but the front stairwell was blocked by flames. According to witnesses, the children at the front broke from the lines and tried "to fight their way back to the floor above, while those who were coming down shoved them mercilessly back into the flames below." Those who made it to the rear exit found it locked. Outside rescuers unlocked it but found it opened inward, so it was impossible to move against the press of dozens of desperate bodies. The fire swept through the hall, springing from one child to another, catching their hair and the dresses of the girls. The cries of the children were dreadful and haunting. The school's janitor, a German-American named Herter, was accused of setting the blaze (though he lost four children in the fire and was badly burned trying to rescue one), and for a time he was detained in protective custody to keep residents from lynching him.

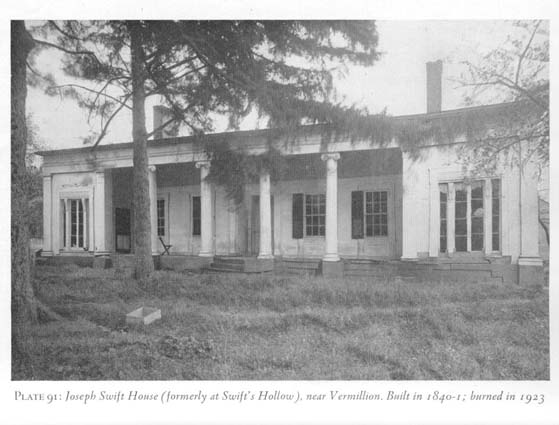

Shortly before the investigation, in 1908, a disaster took place in the town of Collinwood, some forty miles east of Vermilion. 176 elementary school students were burned or trampled to death when they became trapped in a stampede situation and couldn’t escape a fire that was consuming their school. The children began descending down the stairs to the exit after the fire alarm was sounded, but the front stairwell was blocked by flames. According to witnesses, the children at the front broke from the lines and tried "to fight their way back to the floor above, while those who were coming down shoved them mercilessly back into the flames below." Those who made it to the rear exit found it locked. Outside rescuers unlocked it but found it opened inward, so it was impossible to move against the press of dozens of desperate bodies. The fire swept through the hall, springing from one child to another, catching their hair and the dresses of the girls. The cries of the children were dreadful and haunting. The school's janitor, a German-American named Herter, was accused of setting the blaze (though he lost four children in the fire and was badly burned trying to rescue one), and for a time he was detained in protective custody to keep residents from lynching him. Swift’s Hollow is the location most often visited by those seeking a taste of the supernatural. A graffiti covered sandstone column marks the entrance of the area, which contains the foundations of this once magnificent mansion. Today all that remains of the Swift Mansion are sandstone blocks from its foundation. Located deep in the woods, these remnants are now scrawled with graffiti left behind by late night visitors. They stand in the forest like guide stones for all those daring enough to seek an experience of the legend of the Gore Orphanage.

Swift’s Hollow is the location most often visited by those seeking a taste of the supernatural. A graffiti covered sandstone column marks the entrance of the area, which contains the foundations of this once magnificent mansion. Today all that remains of the Swift Mansion are sandstone blocks from its foundation. Located deep in the woods, these remnants are now scrawled with graffiti left behind by late night visitors. They stand in the forest like guide stones for all those daring enough to seek an experience of the legend of the Gore Orphanage. Brownhelm Ohio's Rich History

Brownhelm Ohio's Rich History The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio

The Early Settlers of Brownhelm Township Ohio Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio

Early Life In Brownhelm Ohio The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm

The Grand Old Forest Of Brownhelm Food

Food Wild Animals

Wild Animals Early Education In Brownhelm Ohio

Early Education In Brownhelm Ohio Early Religion In Brownhelm Township Ohio

Early Religion In Brownhelm Township Ohio Brownhelm Ohio Fourth Of July

Brownhelm Ohio Fourth Of July Difficulties & Compensations In Early Brownhelm Township

Difficulties & Compensations In Early Brownhelm Township Township & Village Unite

Township & Village Unite John Mercer Langston

John Mercer Langston The Haunting History of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow

The Haunting History of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow The Real Story of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow

The Real Story of Gore Orphanage & Swift's Hollow